Too many parents cannot help their kids with their math. They want help because their kids cannot understand the math. While I can help in the short term, I am frustrated by the fact that the methods students are given to solve simple math problems are complicated. As far as I know, learning to do math is foundational to learning to do a budget, or knowing which product is more economical. The students aren’t unwilling to learn math, but when they are told that they need to understand numeracy, which is how numbers work, they couldn’t care less. All they want to know is how to get the right answer.

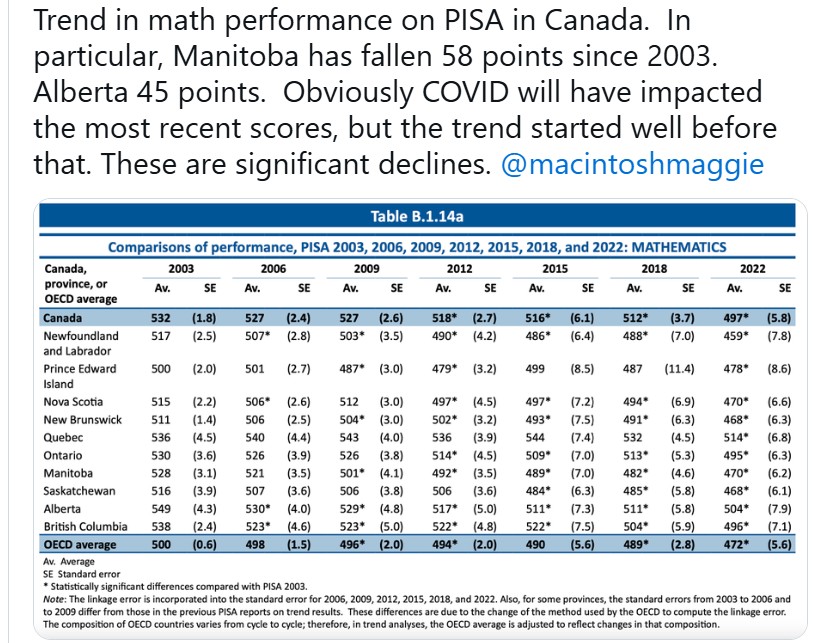

A number of years ago, educators noticed a significant decline in the ability of Canadian students’ abilities in Math. The following chart shows the gradual decline in numerical skill since 2003. PISA is “the most extensive and widely accepted measure of academic proficiency among lower secondary school students around the world” (https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default /files/math-performance-in-canada.pdf).

This chart is from a CBC report in 2023 (https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/canadian-students-pandemic-learning-match-science-reading-study-1.7049681).

There were some declaring that Covid 19 stay-at-home mandates were to blame, but that does not account for the 17 years before that. There are many who don’t want to blame the curriculum or the schools’ administration, and certainly we cannot blame teachers who simply do as they are told. So what is the problem?

Without sounding too condemnatory, one researcher, Anna Stokke, a math professor at the University of Winnipeg, noted the gradual decline. “I do think part of the problem is the philosophy of how to teach math,” Stokke told CBC News. “First of all, we’re not spending enough time on math in schools. And second of all, kids just aren’t getting good instruction in a lot of cases. They’re not getting explicit instruction. They’re not getting enough practice. And that really needs to change.”

This researcher gently pointed to the correct reason for the lack of math success. She says it’s “the philosophy of how to teach math.” At its root is the same philosophy of learning that made non-readers out of half the population. Dubbed “Whole Language Learning” it is also ruining the learning of math. When students were required to understand “concepts” instead of memorizing math facts like the addition and multiplication tables, the focus turned to “discovering” how math works.

According to The Straight Dope, “the main thrust of these changes was a switch from teacher “telling” and student recitation to ‘inquiry’ and ‘discovery,’ with the hope that students would be more likely to retain information they found out themselves than what was just told to them in lecture form and memorized. In the hard sciences, and to a lesser extent the social sciences, this was described as ‘hands-on learning’” (https://www.straightdope.com/ 21342664/what-exactly-was-the-new-math).

I learned this gradually as I tutored students who did not know their times tables and used their fingers to add. Subtraction was a mystery to them, however, and the time taken up consulting their tables of math facts slowed their ability to grasp the concepts. Algebra became a focus for me to tutor because multiplication and division were not well understood in spite of, or because of, the way they were taught. And to do algebra, a thorough understanding of fractions and how to add, subtract, multiply, and divide them, is essential. Most students had only a rudimentary knowledge of what a fraction is.

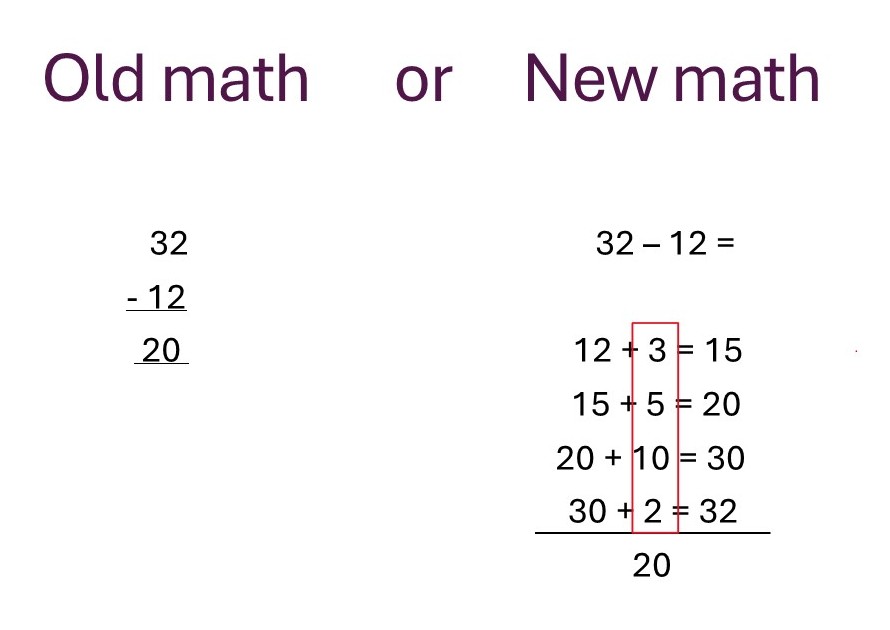

A sample of the new math

Memorization Forbidden

The “experts” say that memorizing math facts is boring and kids don’t like it. Instead, to try to get students to get to the concepts first, they are given sheets of math facts to consult. They have fact sheets for addition and sheets for multiplication, or they are allowed to use a calculator. All they have to do is look the number up each time they need a fact. However, the shift from the fact page or the calculator back to the problem they are working on breaks their focus. They cannot concentrate on the concept because it takes too long. I once tutored a Grade 9 student who was struggling with math. Each time she used her calculator, it was a distraction and she could not remember why she looked up the number. I finally convinced her to memorize her multiplication tables, and by the middle of Grade 10, she was explaining functions to me.

Calculators have also created issues. When I tutored at a university, I met too many who were lost without a calculator. They cannot multiply a 4-digit number by a 3-digit number or even 8 x 9 without it. I had to run many remedial math classes to allow some to take the trades curricula. They quickly learned that they cannot use a calculator unless they know why they are using it.

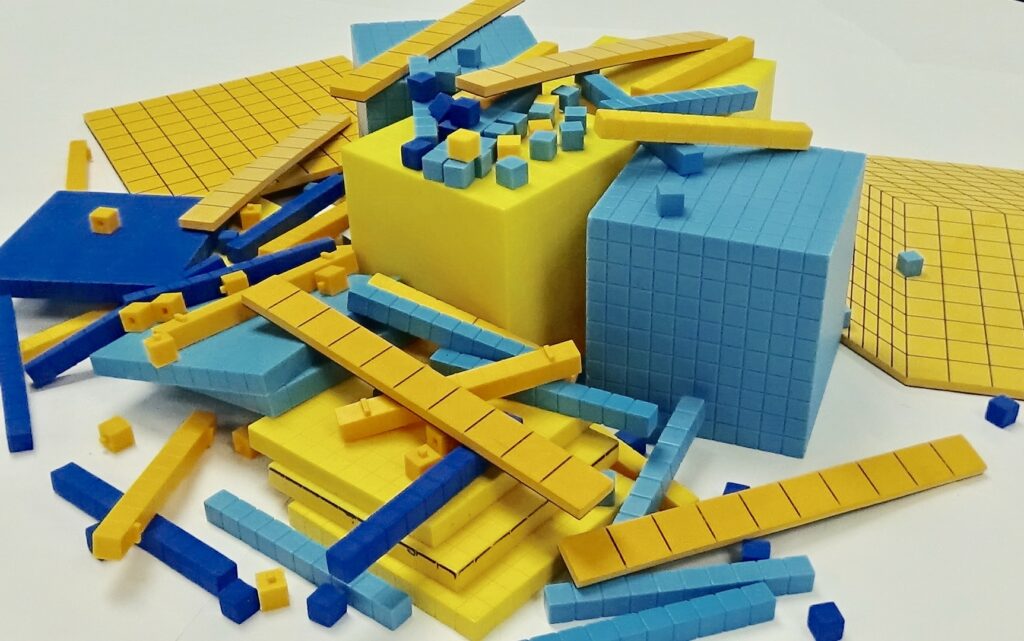

Manipulatives have also become popular. Students take brightly coloured blocks of ones, tens, and hundreds and pile them up or break them into groups according to the problem, and then they count what is created. However, when shown a problem like 15 divided by 3 = ?, they are stumped. No one shows them how to do long division, and while they can divide the groups into smaller groups, what will they do when they no longer have a set of manipulatives? They are allowed to use a calculator, but it does not help them understand how numbers work together. Formulas are torture to them.

One other problem is that the students are not given enough time for their brains to grasp what they are learning. Math takes so much practice to master. I have taught kids who had to understand one chapter of math per day, practising on only 5 to 10 questions. They were expected to learn a whole curriculum in 10 to 12 weeks. If they did not pass a section, they were not asked to repeat it. They were sent through to the next section where they got more lost. Often a parent does not even discover their child is struggling in Math until halfway through the course. The chances of catching up are nil. The students’ attitude becomes one of “I can’t do this”, and this attitude is shared by many of their classmates, so the attitude get worse. They know they are not learning well and they feel stupid. It is unfair to give them a minimal mark and let them pass when they could have learned the material if given more time and practice.

What students need is direct, explicit instruction in math, beginning with the memorization of facts that are the foundation of understanding numbers. The Whole Language method puts the cart before the horse. No one can think clearly about how numbers work until they can quickly recall the facts. Knowledge comes long before understanding. We teach people how to do practical things before we explain why they need to do it that way.

The fallout of this failure of teaching what kids need to learn is the poor results in the PISA scores. The PISA test measures a student’s ability to apply their knowledge to a real-world problem. “It’s about reasoning, interpretation, and critical thinking, not just memorization.” (https://crania-schools.com/blog/how-is-canada-doing-in-math/). Therefore, when a student does not do well in Math, he is limited in his ability to use that knowledge to attain a career that requires good mathematical skills. When they are denied the basics, students have a difficult time catching up, and by high school, they opt for the foundational math programs, leaving the algebra to those they think are smarter.

Let’s give students the tools they need to succeed. Let’s allow them the time they need to really learn deeply. Let’s provide the basics of math before we give them the loftier numeracy concepts. Kids today are just as smart as the previous generations. With the right teaching, they can develop the skills they need to become good math students. https://cdhowe.org/publication/time-to-address-canadas-falling-math-scores/